How to Define Your Organization’s Values or: What Happens When Carl Jung Joins the Marketing Department

Share

When organizations talk about what they believe in, it’s weird. A company, nonprofit, university, etc. isn’t a person, it has no singular moral “self” who would value anything. So how can a group’s values communicate anything authentic? How do you faithfully articulate the shared values of a set of co-workers? Over the past year we’ve been rebranding Kalamuna, and part of that has meant asking ourselves what we value and what of those values we share. In this post I’ll show you how we derived those values in hopes that your organization can use our process as an example of what you might do.

What are “company values” and why would you need them?

A company’s values should motivate and guide the behavior of the people who make it up. In the case of Kalamuna, we, the company members, all know that we value “making a living,” but beyond that, why do we exist as a group? What is it about us that makes us Kalamuna and not Joe’s Web Shop? We could say that it’s our unique position in our market, but how did we even come to inhabit that? Beyond making a buck, why do we exist as a business? No matter what your organization, agreeing on shared values helps you articulate answers to these and other questions. And once you have them, you can use them in many ways. Your values can help guide you through complicated situations, reminding you that you prize X over Y, so X should lead decision making. Values also connect people on certain matters, and help you stand out to and connect with potential partners, vendors and employees. These are just a few reasons values are important.

Don’t make it up. Investigate.

To find out what people at all levels of an organization value and which of those values they think the group embodies, it may seem obvious to just ask them. But, there are problems with the data you get when people self-report on their thoughts, memories, etc. One of these problems is that respondents may feel pressured to say what they think the moderator (in the case of Kalamuna, this was myself) wants them to say, or what they think they should say. We work together, after all–I work on the Kalamuna brand and on the design team for our client work–and there’s no erasing the influence our roles and relationships have on how we share thoughts about the company in whose identity we all have a stake.

To try to mitigate this influence, and to encourage different sorts of responses, I asked a group of eight stakeholders not only to write down words they thought embodied our values, but also to find images that did the same. They had a few days to work on this at their leisure, and an extra five minutes during a video call workshop when they finalized their collages. After the time was up, each participant talked about the words they used and explained how their images represented particular company values. This exercise was a pared-down version of some qualitative research methods I’ve seen big ad agencies use for their private company clients, but you can scale such a workshop for your nonprofit, university, or institutional stakeholders.

One respondent’s values slides

Social scientists, too, administer these projective tests (the Rorschach being the most well-known) in part, because they’ve seen that respondents are more likely to be forthcoming about what they think when they're working with an object that doesn't directly involve them; they’re talking about the thing, an image, a song, a video, etc., not themselves. In fact, some research I’ve come across says that generally, people respond to static imagery more immediately than to text or other forms that demand more thought and interpretation. I asked participants to choose their own images through a Google image search instead of asking them to select images from a pre-selected collection (which I’ve seen done before) because I figured that if they had to search for images they’d be more engaged in the exercise.

Another of the respondents’ values slides

Making sense of the responses

It would have been easy if we’d just pinned one of these slides up on the Kalamuna website with a headline that read “This is what we stand for!” and call it a day. But there were many voices (and slides) to consider. So, how did I process everyone’s varied responses, categorize them, and ladder them up to discrete values on which we could all agree?

I could have picked out the words that appeared most often on the slides, along with the words that came up most often in respondents’ descriptions of their images, and then narrowed down a list of words and call those our values. But not everyone uses the same word to communicate the same meaning. And, making connections between words is subjective. (Do “read” and “red” go together in one category because they make the same sound when uttered?) Without some sort of evaluative criteria, making associations between words veers is just random and poetic.

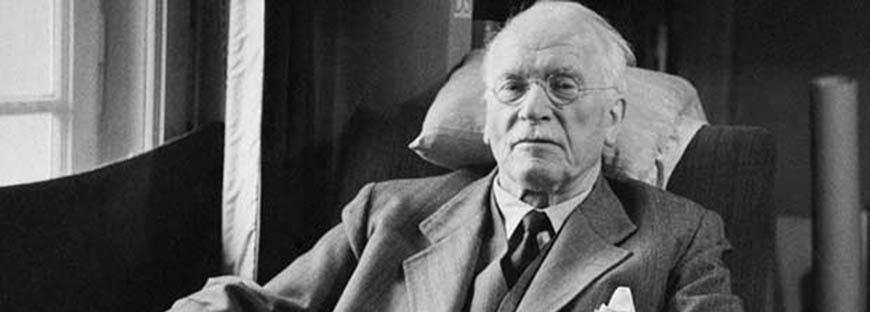

Enter Jung’s Archetypes

In devising an evaluative criteria with which to organize my data, I decided to use the 12 brand archetypes, a common tool of the brand strategist/account planner. It derives from social science, like many advertising practices, and before the archetype became such a device, it was more widely known as a concept of early 20th c. Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung.